In March 2022 the UK government allocated a budget of £39.8 billion to R&D for 2022-2025 to support its Innovation Strategy and is currently beating its target of spending 2.4% of GDP on R&D by 2027, though this is due to an upward revision of the counting methodology for R&D expenditure by the Office for National Statistics (ONS). This is significant as one of a number of government initiatives, but these separate initiatives are not integrated into a coherent national plan. Apart from the UK government using tax incentives to encourage the market to drive changes, there is no strategic framework which could underpin a national industrial strategy. This brief paper addresses three key issues:

- It proposes a new strategic framework based onthe Triple Chasm Model2, which provides a data-driven approach tounderstanding how science and technology-enabled innovation is commercialised. It identifies three ‘chasms’ or hurdles which innovative companies must cross

in order to move into the next growth stage, and identifies the 12 key drivers (meso-economic vectors) which need to be addressed throughout the growth journey. - It maps a representative set of existing UK initiatives against this framework, illustrating the lack of an integrated approach and the absence of any focus on the central translation challenge around Chasm II. It also compares the UK’s approach versus the EU, USA and China, highlighting the different ideological positions and how the UK is an outlier.

- It then proposes the outline of a new Industrial Strategy consisting of 3 key elements:

- An integrated approach based on therelationships between all 12 meso-economic Vectors (and their sub-Vectors and Attributes)

- A deliberate focus on Chasm II, which theTriple Chasm Model identifies as the major hurdle for successful commercialisation

- Articulation of a new ideological orientation, which proposes a new ‘national’ perspective, including a different balance between the roles of the public and private sectors.

Contents

Most attempts to articulate a national industrial strategy are hamstrung by the UK government’s tax incentivised/market driven ideology, lack of clarity in defining the boundaries (both market-based and geographic) within which the strategy applies, and confusion about the actual drivers which govern growth throughout the growth journey.

Industrial strategy does not happen in a ‘national’ bubble,but depends on other economies, hence the need to understand the limitations of national regulatory controls, the ideological stance of its policy makers and ideas about technological sovereignty.

It is also important to clearly distinguish between technologies, market spaces and the industry sectors that the industrial strategy is addressing and supporting.

Our response to this challenge is based on adopting a newstrategic framework based on the data-driven Triple Chasm Model which describes the process by which science and technology-enabled ideas are translated to create products or services that deliver commercial impact.

The strategic framework consists of three elements:

- Definition of the maturity of any proposition(product or service)

- Defining the different drivers of growth (the meso-economic vectors) which govern the translation journey

- Integrating the maturity and growth drivers to define a Commercialisation Canvas

This framework provides businesses with the context to test their own strategies.

The Product or Service provides the primary unit of analysis used in the derivation of the Triple Chasm Model. Multiple Products can then be aggregated to create assessments at the level of Companies and other types of Organisations. Multiple Companies (and Organisations) can then be aggregated to tackle Market Spaces (and sub-market spaces). Finally, Market Spaces can be aggregated to define the National Picture. The power of this aggregation approach is that allows system boundaries to be defined explicitly, with the potential to understand the porosity of boundaries subsequently.

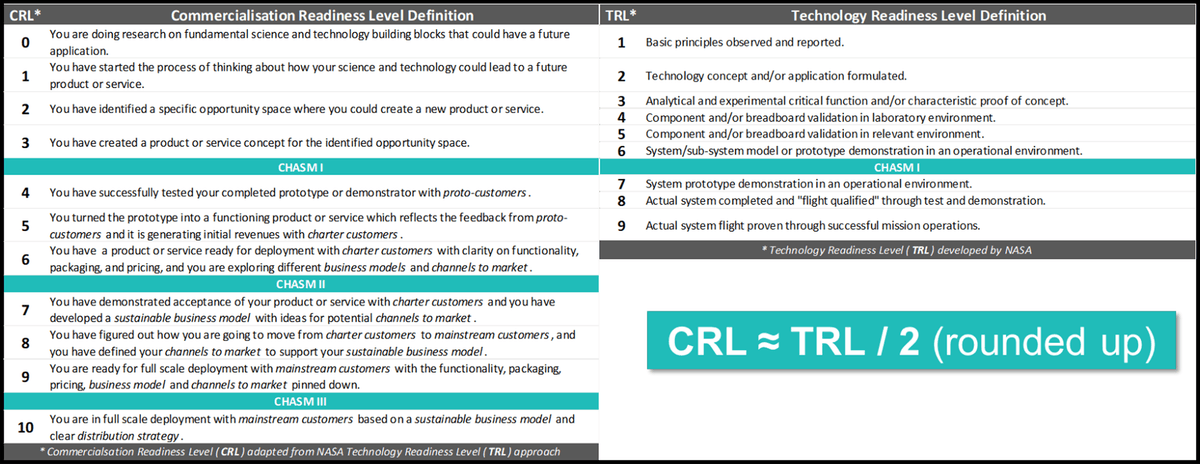

We use Commercialisation Readiness Level (CRL) instead ofTechnology Readiness Level (TRL) which is more commonly used by technology researchers because TRL only partially addresses the commercialisation journey, as Figure 1 illustrates. This CRL-based maturity assessment plays a critical

role in addressing any commercialisation challenge in terms of the starting point, the desired endpoint and the gap which needs to be addressed. This CRL mapping explicitly defines the 3 chasms in the commercialisation growth journey. The TCM research confirms that the biggest challenge on this growth journey occurs around Chasm II, the scale-up chasm.

Figure 1: Defining Commercialisation Readiness Level

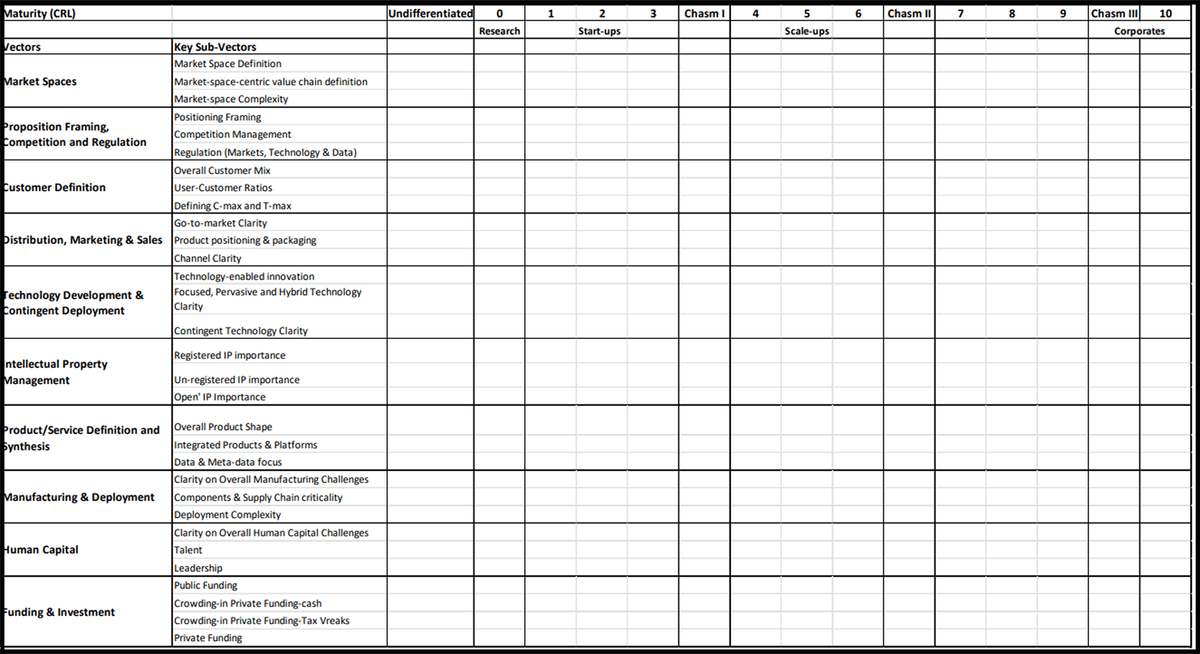

Throughout the commercialisation journey for a product or servicethere are 12 drivers (or meso-economic Vectors) that need to be addressed with differing levels of priority depending on the CRL that the product or service has achieved.

As shown in Figure 2, these drivers are:

- 4 ‘external’ drivers: Market Space; Proposition Framing, Competition & Regulation; Customer Definition; Distribution, Marketing & Sales.

- 6 ‘internal’ drivers: Technology Development; IP Management; Product/Service Synthesis; Manufacturing & Deployment; Talent, Leadership & Culture; Funding & Investment.

- 2 ‘composite’ drivers: Commercialisation Strategy; Business Model.

Figure 2: The 12 meso-economic Vectors

By integrating the maturity descriptors of the commercialisation journey with the drivers on the commercialisation canvas, it is possible to map the coverage of any product, company, market space or geographical region. Such insight can provide a powerful basis for leaders to make decisions

about the allocation of key resources in a time-critical manner.

The x axis of the Commercialisation Canvas is defined by the Commercialisation Readiness Level

(CRL).

The y axis of the Commercialisation Canvas is defined by the12 Vectors, Sub-Vectors and Attributes.

The full Commercialisation Canvas constitutes nearly 200 variables, so we use a Condensed Version of this Canvas, as shown in Figure 3, which covers all 12 main Vectors and the Key Sub-Vectors to generate a more manageable Canvas to articulate Industrial Strategy.

Figure 3: The Commercialisation Canvas

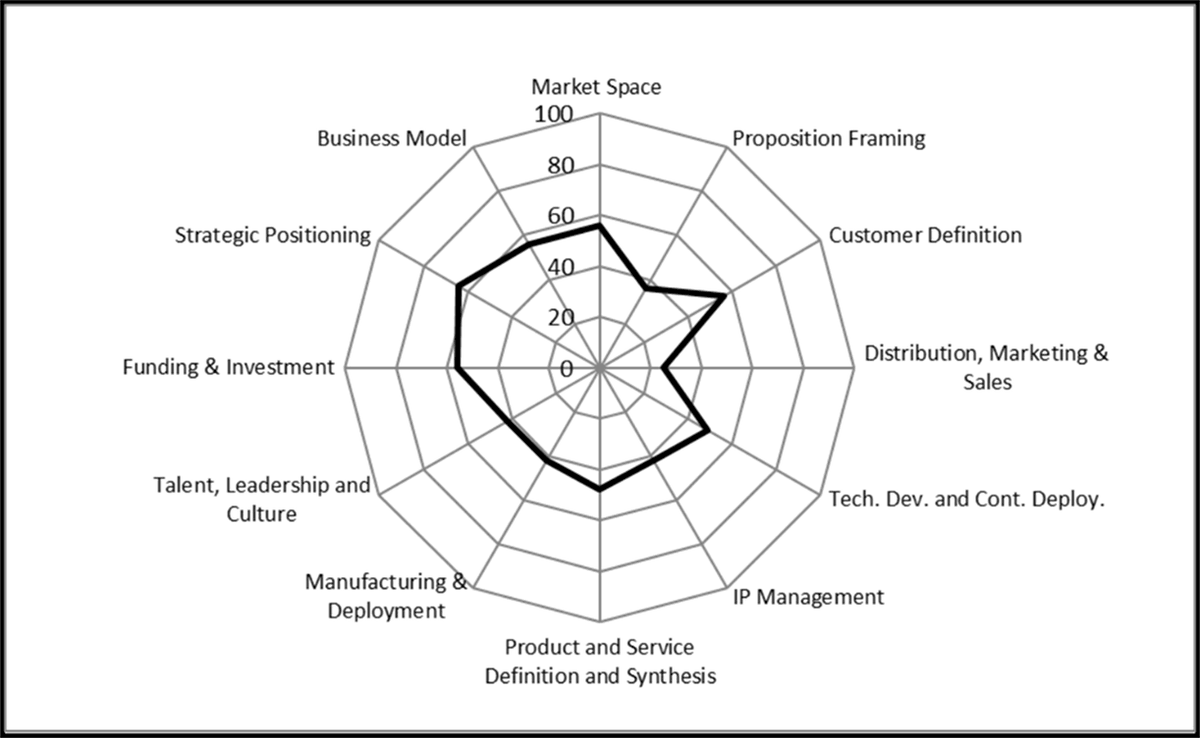

The challenge in quantifying the relative importance of different Vectors, sub-Vectors and Attributes is the need to manage heterogeneous units of measurement. We tackle this by using the performative

Commercialisation Intensity Metric (defined in TCM) to map the relative importance of different initiatives on the Commercialisation Canvas. For example, Commercialisation Intensity can be used to map the relative importance of a typical product around Chasm II as shown in Figure 4.

This map enables us to map current activity, identify gaps, and to make recommendations for areas any new industrial strategy needs to address, at a high level.

We can then expand on this picture to create specific recommendations where we can disentangle initiatives focused on technologies (for example, AI) from market spaces (for example, healthcare) or conventional industry sectors (for example, semi-conductors, which cover different technologies and market spaces).

Figure 4: Commercialisation Intensity for a Product at Chasm II - an example

We can also use the performative metrics data to understand the difference in industrial strategies of different countries and groups of countries based on how they treat the different vectors.

The UK Government has oscillated between a number of positions over the last decade, ranging from a resistance to any kind of industrial strategy, a short-term embrace with the desire to articulate

national priorities, and culminating in the current position, which emphasizes a belief in the primacy of market forces coupled with an aversion to state intervention more generally. This has not prevented general commitments to supporting strategic technologies, which have always been caveated with a

desire not to ‘interfere in the workings of the market’.

As a result, any analysis of the UK needs to start with an explicit understanding of the ideological orientation, because important international variations have emerged in this space, particularly from other countries which historically embraced the primacy of the market, like the USA.

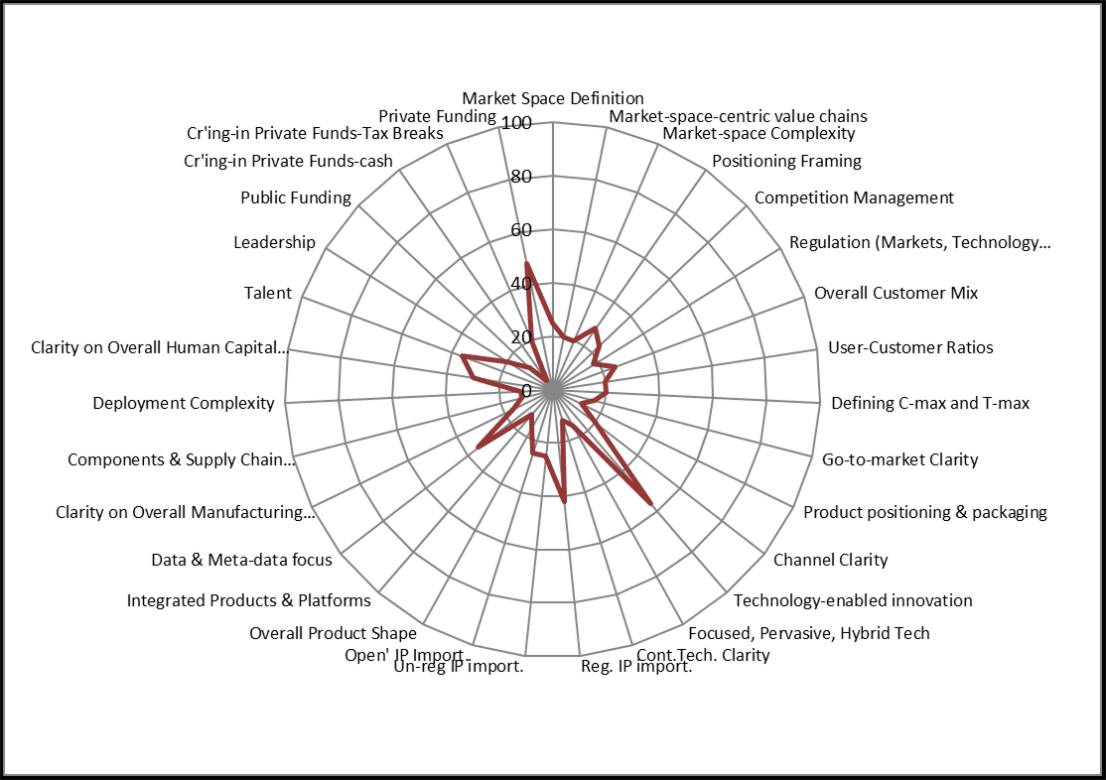

When it comes to commercialising innovation, the UK’s current overall ideological orientation is out of step with other leading (eg G7) economies, with a singular emphasis on the primacy of ‘the market’ and the pre-eminent role of private capital in the commercialisation process; this sometimes sits uneasily beside government-led funding for early-stage research and development. As shown in Figure 5, this position can be summarised as follows:

- Strong focus on the role of private capital in supporting the commercialisation process, with state financial intervention largely restricted to supporting favourable tax regimes; this approach avoids use of public funds to ‘crowd-in’ private funding except in a limited number of situations, typically involving large corporations

- Preference for a light-touch regime when it comes to regulation and competition policy

- Despite statements about not picking winners, a focus on selecting key technology areas when investing in research & development (mainly in academia and early-stage start-up players)

- Strong IP Management regime

- A (newly discovered) passion for looking at Data (and meta-data) in the formulation of new products and services

- Continuing commitment to building the science and technology Talent base

This coverage is different from other major global players, particularly in treating all the other vectors as being less important in the context of national industrial strategy.

Figure 5: Current UK Ideological Orientation

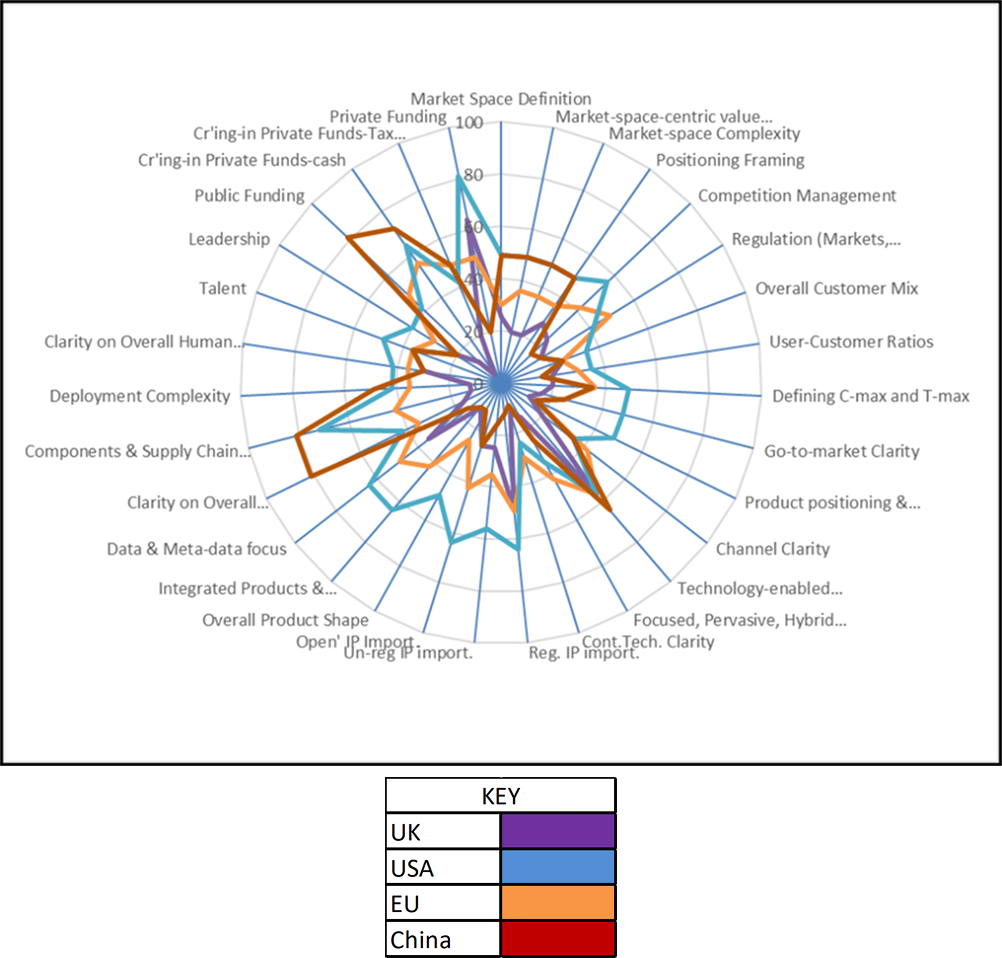

The contrast between the UK and other major industrial players is quite sharp, when viewed through the lens of ideological orientation. The key differences, shown in Figure 6, can be summarised as follows:

- Given the previous historic affinity between theUK and US science and technology commercialisation eco-systems, the major surprise is how the USA (as explicitly articulated in the Inflation Reduction Act3 ) has now embraced virtually all the Vectors involved in the Commercialisation process

- In particular, the USA is now firmly committed to providing significant public sector funding to building the science and technology base and the commercialisation engine, which includes a commitment to using public money to ‘crowd-in’ private investment in strategic areas

- The IRA also comes with a strong policy commitment to addressing all the commercialisation Vectors, with a particular emphasis on manufacturing & deployment

- In overall terms, there is a warm embrace for looking at all these Vectors from a Green (or Sustainability) perspective so that, for example IP Management, Competition Policy and Regulation are addressed in a joined-up way.

- The EU approach to industrial strategy is quite similar to the US now, with a strong policy commitment to managing the impact of all Vectors. The only difference in emphasis affects two areas

- When it comes to funding and investment, Europe believes that public funding is more important strategically, especially given the relative weakness of European capital markets compared to the US

- The EU’s new Green Deal4 has a stronger commitment to sustainability orientation across all Vectors.

- China’s ideological orientation has not changed significantly over the last decade and shows, as expected, a strong focus on public funding, understanding complex value chains, distribution channels coupled with manufacturing and strong supply chains. This orientation is made explicit in the Chinese government’s Belt and Road Initiative5.

Figure 6: Comparing UK Ideological Priorities vs the EU, USA and China

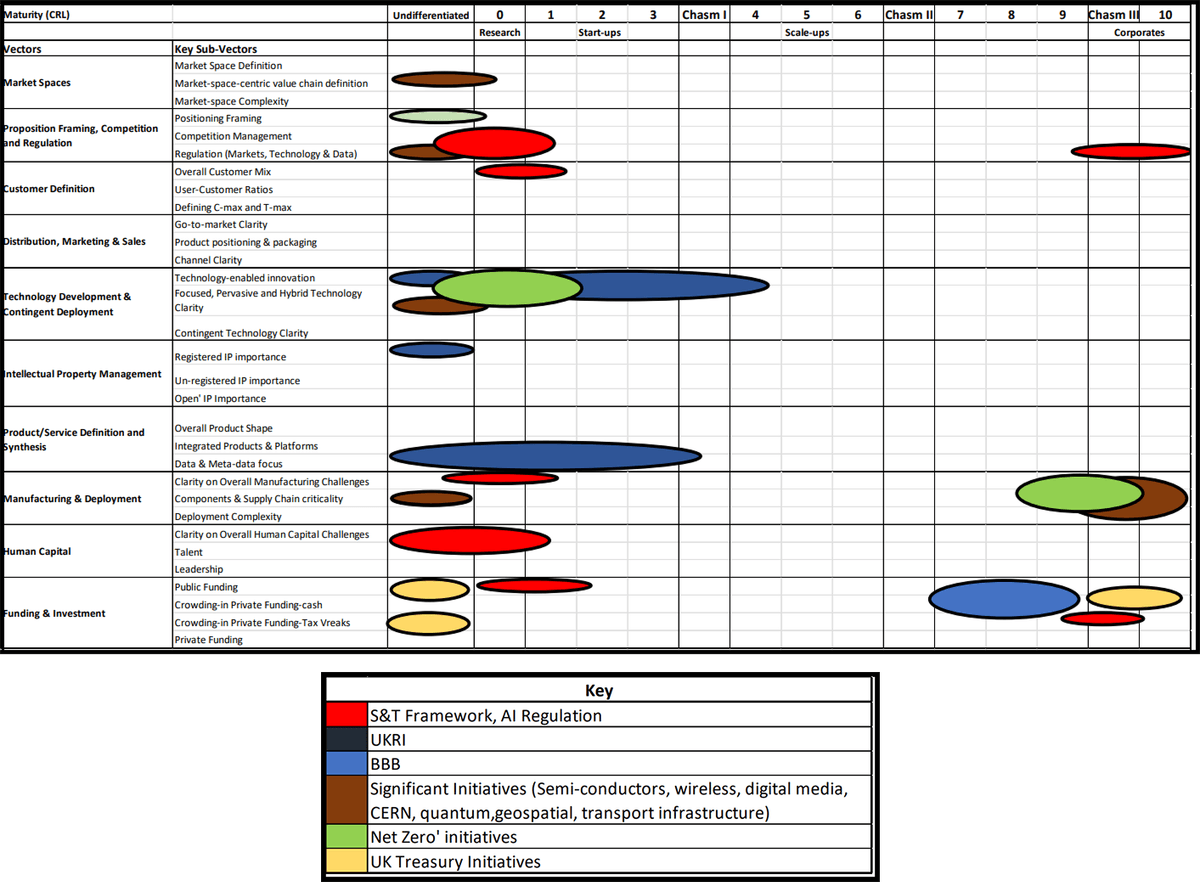

There is no consolidated UK Industrial Strategy so, as a proxy, it’s necessary to analyse a representative set of programmes published by individual government departments. The results of this are shown in Figure 7.

The current coverage of UK Government programmes can be summarised as follows:

- The major UKRI programmes are focused on the creation and early development of a range of critical technologies, defined by a series of white papers, all consistent with international thinking on the technologies likely to produce significant commercial impact. The bulk of this investment is provided to university-based research teams and early-stage commercialisation activity (CRL=0 to CRL=3, 4)

- Strategic policy initiatives are also largely focused on these early stages of commercialisation, with frequent laments about the need to tackle translation, which are largely un-heeded

- There are a number of major initiatives aimed at building and deploying new infrastructure but this support is largely provided to large corporations

- There is a serious gap in the ‘middle’ part of the commercialisation journey, which the Triple Chasm Model has identified as the Chasm II (Scale-up) challenge, as evidenced by studies published by the ScaleUp Institute6.

- The role of the UK Treasury is largely confined to ‘demand-side’ measures aimed at making the UK an attractive environment for private investors; even initiatives such as the British Business Bank are seen through this lens rather than building (new) national capacity.

- Finally, this mapping illustrates the sparse coverage across the 12 vectors, with very little evidence of integrated thinking (it is also worth noting that most of the so-called levelling-up initiatives fail to understand the importance of system boundaries and porosity, and so miss the opportunities to build new regional eco-systems).

Figure 7: Representative UK Programmes mapped against the Commercialisation Canvas

Using the new analytical framework summarised in Part 1 and the absence of an integrated industrial strategy discussed in Part 2, we suggest how the UK could design a new Industrial Strategy to compete in the global marketplace.

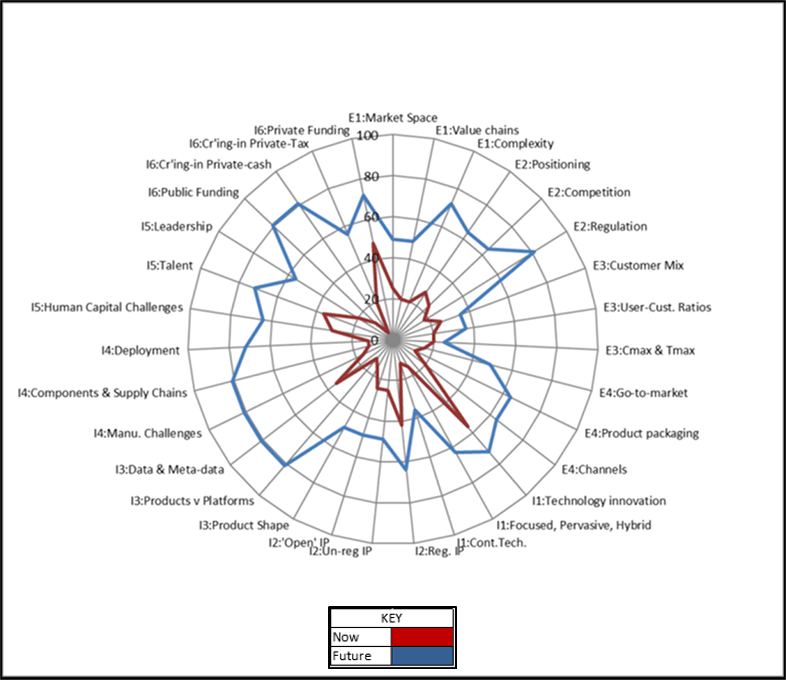

The UK needs to explicitly define a new ideological orientation based on a commitment to a Green Future, which means balancing the competing imperatives of Profit, People and Planet. There is already a significant body of research and guidance available, ranging from the major report on biodiversity7 to the economics of sustainability8. What is missing is an integrated policy perspective which pulls all this together, in the way that the USA’s IRA and the EU’s Green Deal do. This

overall ideological orientation can then drive policy priorities, specific initiatives, and an overall framework to define, measure and optimise impact. Figure 8 shows the current situation and postulates a potential new ideological orientation, which can then be translated into strategic priorities, including funding.

Figure 8: Proposednew Ideological Orientation for the UK

The analysis of current UK coverage clearly shows the serious gap in intervention support around Chasm II - the great translation challenge. We need to design new interventions which specifically address this gap - the Catapults were originally intended to tackle this gap but poor understanding of this gap has resulted in them largely replicating existing UKRI initiatives.

Our analysis suggests that the development of a new industrial strategy for the UK should focus on the following elements

- The UK needs to adopt an explicit ideological orientation (as others seem to be doing) which incorporates the following elements:

- Create an integrated approach to industrial strategy based on the shape of support based on all 12 Vectors, not just a few (for example, funding and investment).

- Avoid an approach based on technological determinism (such as ARIA) and a narrow focus based on currently ‘fashionable’ technologies.

- Avoid an approach based on current perceptions of industry sectors, rather than the evolution (and revolution) in market spaces, eg in Healthcare with stratified and personalised medicine leading to dramatic changes in delivery pathways.

- Define a unifying theme which can bring this integrated approach to life -the ‘green’ theme, but unpacked to talk about Profits, People and Planet.

- Strong new focus on Chasm II in the Commercialisation Journey (our mapping shows the clear gap here in the UK), with the following implications:

- This could become a key strategic differentiation.

- Divert some existing funding from early-stage commercialisation and/or create new funding for Chasm II.

- Understand the implications for Funding & Investment and Treasury orthodoxy around funding models (cf Mansion House speech re Pension Funds9); also recognise that the VC model is broken10.

- Define key strategic market spaces based on the above, in particular the following implications:

- This means strong focus on selected key marketspaces (with less strong focus on other areas?).

- Market space focus rationale based on focusing on complex market spaces, characterised by significant changes in market-space-centric value chains leading to new, bigger opportunities.

- Understand how the Manufacturing & Deployment vector needs to be assessed in an integrated way not as an afterthought.

- We would suggest the following key market spaces:

- Healthcare & Lifesciences

- Agriculture & Food Systems

- Energy Systems (Conventional & Renewable)

- Transport, Logistics, & Infrastructure

- Media & Entertainment

- Computing & Electronic Devices

Notes:

1. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-innovation-strategy-leading-the-future-by-creating-it

2. Triple Chasm Model https://www.triplechasm.com/how-we-help/triple-chasm-model

3. Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inflation_Reduction_Act

4. EU Green Deal https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en

5. Beltand Road initiative https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Belt_and_Road_Initiative

6. https://www.scaleupinstitute.org.uk/

7. Final Report - The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

8. Implementing the SustainableDevelopment Goals - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

9. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/mansion-house-2023

10. Venture Capital Is Broken—But Who Can Really Fix It? | Observer