1. The Challenge

There is general recognition that macroeconomic theory is inadequate when it comes to understanding growth - but most responses to this challenge so far have been largely inadequate.

This weakness has been recognised and studied by many leading economists in the field but the precise challenges were very clearly articulated in the collection of essays on ‘Rethinking Capitalism’ edited by Mazzucato and Jacobs, containing contributions from several leading economists.

In their introductory essay for this collection, Jacobs and Mazzucato summarise the three main challenges in understanding the growth challenge:

‘Firstly, we need a richer characterisation of markets and the businesses within them …markets are better understood as the outcomes of interactions between economic actors and institutions…

The second key insight is that investments in technological and organisational innovation, both public and private, which are the driving force behind economic growth and development. The diffusion of such innovations across the economy affects not just the patterns of production, but of distribution and consumption…. But this requires a much more dynamic and accurate understanding of how innovation occurs than is provided by orthodox economic theories…

Recognition of the role of the public sector in the innovation process informs the third key insight. This is that the creation of economic value is a collective process.’

2. The Macro-meso Framework

These astute observations point to the urgent need to develop a rigorous meso-economic approach to understanding growth—the RDS has set out to provide this approach and to apply it to the UK economy to drive the growth agenda.

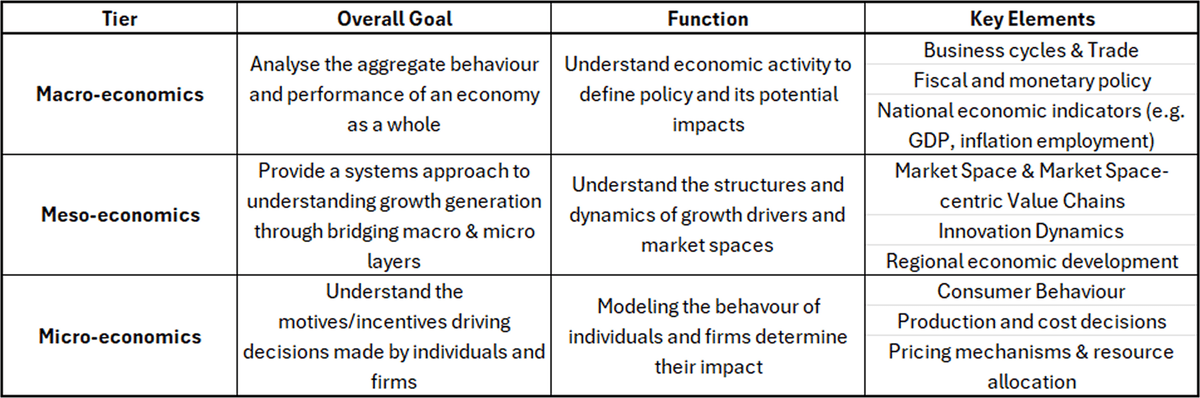

Economic theory typically considers the economy through three main levels of analysis, macro, meso, and micro, each focusing on different units and scales of economic activity as summarised in the table below:

Figure 1: The 3 Levels of Economic Policy Analysis

The meso-economic level is essentially a “translational layer” that connects individual firms (micro) with whole industries/economies (macro). It focuses on the innovation ecosystems—clusters, sectors, supply chains, and value networks—within which firms operate, and which are increasingly being recognized as vital for understanding economic complexity, innovation, and structural change.

Creating a meso-economic framework is difficult because it requires finer granularity of approach coupled with collecting a large body of data and then understanding patterns of (emergent) behaviour that is not grounded in current macroeconomic orthodoxy.

The RDS identified that the most suitable model for doing this currently is the Triple Chasm Model, which was built using global data, covering many different ecosystems, thousands of companies and tens of thousands of products spanning different markets and customer types.

The Triple Chasm Model is built from the ground up and uses the product as the primary unit of analysis. This product data can then be aggregated to understand companies (with multiple products), market spaces (with many companies) and ecosystems (which consist of market spaces and other players that enable market operation). For each product, the data consisted of over 50 variables, and their temporal variation, which can characterise the behaviour of the product.

The key elements of the meso-economic approach are:

- Developing a new measure for the maturity of any product defined as the Commercialisation Readiness Level (CRL)

- Defining 12 main meso-economic drivers of growth based on k-means clustering of the data from the 50+ variables

- Defining the commercialisation journey for any product, calibrated by market spaces with explicit market-space-centric value chains.

The challenge, however, is using this meso-economic model to understand industrial policy, strategy, and execution planning and to link the traditional macroeconomic policy levers to meso-economic vectors. Therefore, a robust framework is required that can describe the macro-economic levers and apply them consistently in an environment where the ideological priorities of governments can change but need to be specified precisely.

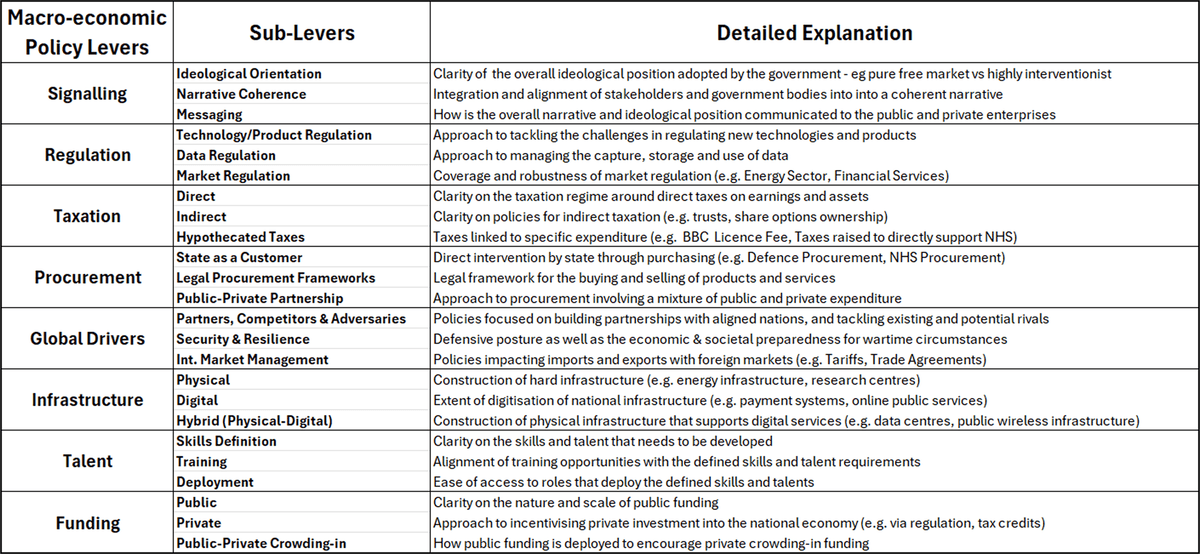

Figure 2 below shows the full set of macro-economic levers which typically describe all aspects of macro-policy making, although in some scenarios, some of these levers may not be seen as relevant or treated differentially in terms of importance.

Figure 2: Macro-economic Policy Levers

This framework highlights the full set of levers which, in theory, should be available to policymakers working in a macroeconomic environment, but in reality, some of these can assume more importance than others, based on ideological orientation, which may not always be explicitly declared.

What this highlights is the need for clarity in ideological orientation, which while not always expedient to declare – is necessary to delivery policy with speed and rigour. It is helpful to unpack each of the levers and associated sub-levers.

Signalling plays a critical role in guiding the behaviour and compliance of all the actors. Here the government has and continues to struggle, with little clarity on the ideological orientation of their political project beyond notions of growth. Government departments appear poorly aligned with each other and public messaging is often confused and sidetracked by unforced errors.

Regulation has become increasingly important, particularly in the realm of data collection and use. It is unfortunately common that regulation of technologies, products and markets fails to consider the unique characteristics of each domain individually.

Taxation policy was given significant coverage throughout the UK’s 2024 general election campaigns. Prominent discussions around capital gains and windfall taxes demonstrate the significance of this policy lever to the business community. And while true hypothecated taxes within the UK today are rare, linking tax increases to improving specific public services can provide valuable political capital.

Procurement appears to have been given more focus in recent government publications although the implementation of the new policies is yet to be seen. In the defence sector, there are clear directives to improve the manner in which government supports new companies through more streamlined procurement, although the approach to life sciences may show this understanding is inconsistent across departments. Managing the balance between public and private partnerships is therefore a significant concern, though UK legal frameworks generally remain competitive.

Dramatic shifts in the USA, Europe and beyond have made geopolitical factors vital to the successful management of the country. With previously well-established alliances left uncertain, a clear vision of how the country partners, competes and combats other states must cover all aspects. Security and resilience have become clear considerations for the government as have considerations for international markets.

Infrastructure is a key lever which requires macro-economic clarity about ownership and cost of use. Physical and digital infrastructure have long been recognised as critical assets that need government support but “hybrid” infrastructure that supports digital services and generates compute for emergent technologies is becoming increasingly important.

The talent and skills agenda sit high on the list of priorities, but the real challenge remains between rhetoric and reality. With much of the implementation of the skills agenda devolved to strategic authorities, the training and deployment of new talent will need carefully calibrated support.

With UK public sector debt placing it in a critically vulnerable position, finding funding to support existing public services and drive new growth is particularly challenging. Crowding-in funding through public-private partnerships still needs greater clarity on how the necessary scale of investment can be incentivised.

All those macroeconomic levers reflect the overall ideological orientation of any policy, but the problem is translating these broad levers into their impacts on the meso-economic vectors at the level where policies are actually implemented.

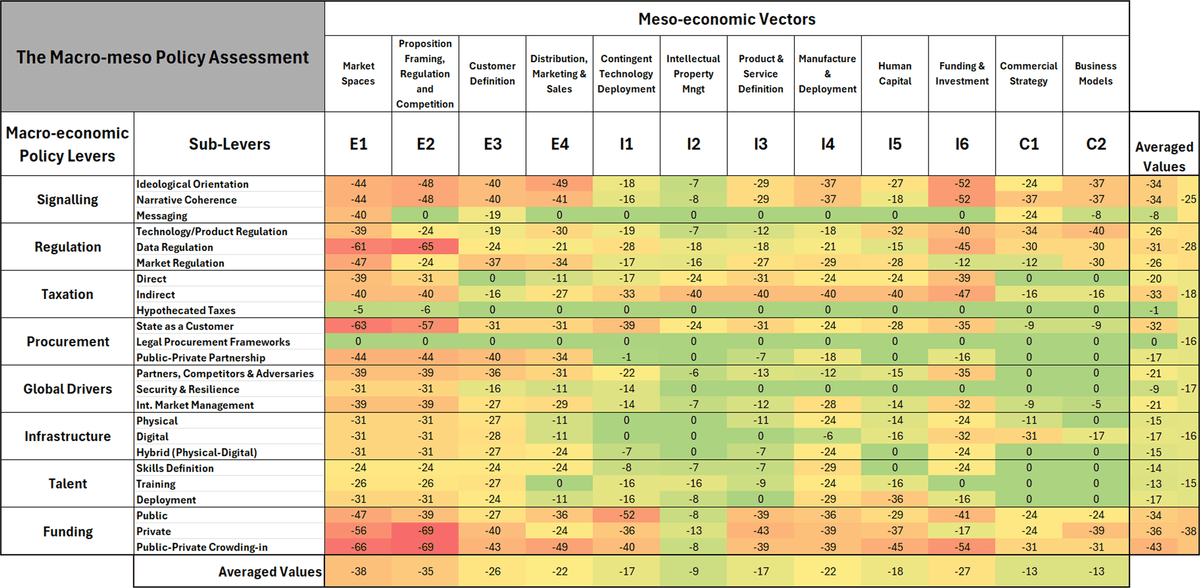

Figure 3: Assessment of Gap Between current UK Government Policy & Target

(Developed by Ad hoc Panel Convened by RDS)

The key to effective industrial strategy, therefore, lies in mapping the macro levers versus the meso-economic vectors, so we can make these relationships explicit because there isn’t a one-to-one relationship between the two layers -but the patterns of behaviour can form the basis of more robust evidence-based approach to understand commercialisation and hence growth.

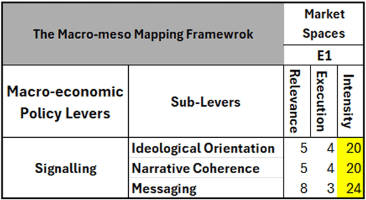

The detailed performative metrics associated with the meso-economic model discussed above should eventually enable a very finely nuanced approach to defining and executing any interventions — but this will need to wait until more detailed research data is available. However, this initial mapping can already provide some understanding of where the challenges lie. Convening an ad hoc panel of experts on issues of UK industrial policy, the RDS scored the government’s current industrial policy. Each policy lever was marked out of 10 for its relevance to each meso-economic vector, as well as assess the current quality of the execution for the component and were combined to produce a value out of 100 for commercial intensity.

Figure 4: Example Assessment of Signalling impact on Market Spaces

This same panel then conducted a similar assessment to construct a new proposed strategy which could be compared with the existing platform. The gap between the two sets of values, shown in Figure 3, reveals a nuanced picture of the areas where government performance is succeeding and failing at driving growth. This sort of analysis could prove to be a valuable tool in designing strategic interventions.

3. Applications of the insights from the macro-meso mapping model

The power of this macro-meso mapping approach can be illustrated by looking at some typical application areas which are currently generating debate.

3.1 UK Industrial Strategy

The recently published UK Industrial Strategy marks a welcome change from the past, where even the idea of a national strategy was not supported by government. The RDS has provided an extensive critique of the new approach, but several key things stand out, which illustrate the urgent need to understand the linkage between macroeconomic policy and the meso-economic vectors:

- The emphasis on the earlier stages of the commercialisation journey -see for example this blog discussing the risks of becoming an incubator nation

- The weak coverage of the 12 meso-economic growth vectors, with a fixation on technology and funding. While funding remains a significant challenge, our analysis shows that technology development is relatively effective by comparison. Market space understanding and customer definitions are two of the least covered meso-economic vectors

- Failure to effectively balance the different macro-economic levers. While policy levers in talent and procurement may be comparatively well managed, signalling, regulation and funding continue to fall short

3.2 The AI Challenge: Technology Sovereignty & Regulation

Probably one of the most challenging areas where the macro-meso framework could be applied is around the whole area of the development, deployment, and regulation of AI technologies, because it exemplifies the challenges of understanding the linkage between contingent technology deployment (Vector I1), market spaces and the value chains associated with them (Vectors E1 and E2), the nature of products and services, the associated data and content, and how they are regulated (Vector I3). This has important implications for technology sovereignty, regulation, and international trade, not to mention issues around manufacturing and deployment.

The typical macroeconomic approach to this is unlikely to provide the basis for any evidence-based and structured approach. The recent conflict at the Turing Institute between the leadership and government priorities highlights the confusion that can arise from the lack of coherence between macro levers and meso-economic vectors. The Turing Institute was originally conceived from a strong technology-centric perspective, centred around the contingent deployment of AI technologies, as encapsulated by Vector I1 in the meso-economic model. This defined the overall ethos and approach of the organisation with strong buy-in from the team.

The reality of course is that the practical application of AI depends strongly on understanding specific market spaces and the products and services within them, as encapsulated by Vectors E1, E2 and I3 in the meso-economic vector model, because this is where the ultimate value (or return on investment) is created. This naturally led the team to look at a range of market spaces where fundamental advances in AI could be deployed. Recently, presumably under pressure from the defence and security strategy, the government, who ultimately funds the Turing, decided to narrow the remit and insist that the Turing should focus on defence and security applications of AI.